is Moshiach. If he then goes on to build the Temple and gather all Jews back to

Israel, then we will know for sure that he is Moshiach.

is Moshiach. If he then goes on to build the Temple and gather all Jews back to

Israel, then we will know for sure that he is Moshiach. The following is taken from WELLSPRINGS magazine. WELLSPRINGS is aimed at highly educated but not necessarily religious Jews, and contains in-depth articles about Jewish philosophy and practices.

Wellsprings is published quarterly and costs $15 per year. Wellsprings Club Members receive holiday guides and discounts at Jewish Discovery Weekends at $20. Subscriptions are available from:

Wellsprings Magazine

770 Eastern Parkway

Brooklyn, NY 11213

(718)953-1000

(c) 1992 Wellsprings

Belief in the coming of the Moshiach (Messiah) is a long standing and integral part of Judaism. The Bible, especially in the prophetic texts, is filled with references to the Messianic redemption. The Talmud and midrashim also contain many discussions about the nature of Moshiach and the messianic era. Maimonides codified belief in the Moshiach as one of the essential principles of Jewish faith. At the beginning of his Mishneh Torah, he writes that "one who does not believe in him, or who does not await his coming, denies not only the prophets, but also the Torah and Moses our Teacher."

The Jewish liturgy is filled with prayers for Redemption and the coming of the Moshiach. One finds several in the text of the Amidah which, together with the Sh'ma, ("Hear O Israel") is the most important Jewish prayer, and is recited three times each day.

The Lubavitcher Rebbe has recently called for a renewed awareness of and emphasis on the idea of the Moshiach's coming. Efforts to do so have elicited reactions ranging from enthusiasm to suspicion to intense opposition.

To clarify the meaning of Moshiach, WELLSPRINGS asked a scholar of contemporary Jewish thought and literature to engage a Lubavitcher rabbi in a discussion addressing some of this discomfort.

SUSAN A. HANDELMAN - is a professor of English at the University of Maryland, and a contributing editor to WELLSPRINGS. She is the author of Fragments of Redemption: Jewish Thought and Literary Theory in Benjamin, Scholem and Levinas. MANIS FRIEDMAN - is a rabbi and Dean of Bais Chana Institute for Jewish Studies in St. Paul, MN. He lectures widely on the Torah approach to contemporary social issues and serves as simultaneous translator for the Lubavitcher Rebbe's addresses that are broadcast internationally.

HANDELMAN: The Lubavitch movement has recently created quite a stir with its renewed emphasis on the coming of Moshiach. What does it really mean to say that "Moshiach will come"?

FRIEDMAN: The ultimate authority on that is Maimonides. Maimonides

says that there will be a Jewish leader who will be a descendant of King David who will

bring Jews back to Judaism, and who will fight G-d's battle. If he does so, we can assume

that he  is Moshiach. If he then goes on to build the Temple and gather all Jews back to

Israel, then we will know for sure that he is Moshiach.

is Moshiach. If he then goes on to build the Temple and gather all Jews back to

Israel, then we will know for sure that he is Moshiach.

Now this means that Moshiach comes not by introducing himself as Moshiach. Moshiach is a Jewish leader who does his work diligently and accomplishes these things. So Moshiach comes through his accomplishments and not through his pedigree.

HANDELMAN: In other words, does the coming of Moshiach mean that we make this "assumption" about a certain person, but the person doesn't himself declare it - and then one day this person finally says, "It's me"? Or does the candidate actually have to go and build the Temple in Jerusalem?

FRIEDMAN: Maimonides says that once he builds the Temple and gathers Jews back to Israel, then we know for sure he is Moshiach. He doesn't have to say anything. He will accept the role, but we will give it to him. He won't take it to himself. And his coming, the moment of his coming, in the literal sense, would mean the moment when the whole world recognizes him as Moshiach.

HANDELMAN: What specifically does that mean?

FRIEDMAN: That both Jew and non-Jew recognize that he is the responsible for all these wonderful improvements in the world.

HANDELMAN: What will those wonderful improvements in the world be?

FRIEDMAN: An end to war, an end to hunger, an end to suffering, a change in attitude.

We're also talking about Moshiach being a change in attitude: instead of people tending towards the evil, we start to tend towards the good. Instead of evil being the primary mover and shaker, good becomes the primary mover and shaker. Now, how is that going to happen? Who's going to cause that to happen? Somebody is generating a kind of new energy that's making people think differently and feel differently and see things differently.

HANDELMAN: Yet isn't it collective Israel, i.e, all the Jews in the world who are having to do their part in that endeavor? Why maintain that it's just one person who is putting out this energy. And how does the person do that?

FRIEDMAN: Everybody has a little bit of Moshiach in them, but still, there is the one who is Moshiach. I think that everybody in Moshe's generation was a little bit like him.

HANDELMAN: How so?

FRIEDMAN: They all received the Torah, they all heard G-d speak face to face, so they had certain qualities that are unique to Moshe, and because they were his generation they shared those qualities. In our generation, we all share a quality that resembles Moshiach. But there must also be a Moshiach. This idea that there is a Messianic era without Moshiach is like the 60's without Bob Dylan.

HANDELMAN: If I am to agree with you that this is the Messianic generation, what would this quality be?

FRIEDMAN: Number one is teshuva [returning to G-d]. There has to be something about the people of Moshiach's generation that helps produce the Messianic benefits. Teshuva is definitely a phenomenon unique to our generation.

HANDELMAN: Why is teshuva an essential quality of Moshiach?

FRIEDMAN: Let's compare it to a relationship. G-d makes certain overtures: G-d chose us, G-d took us, G-d gave us, G-d taught us, G-d protected us. Moshiach means the time when we respond to Him.

HANDELMAN: "Teshuva," in Hebrew, also literally means "response," or "answer" as well as "return."

FRIEDMAN: Right. Not teshuva as regret for the past, but teshuva meaning, "You've done for us, and now we're responding to You." And that is the conclusion or the consummation of a relationship.

HANDELMAN: Yet, hasn't it been the case that in other historical eras the Jews have responded to G-d - indeed returned to G-d with more devotion than they have in this generation?

FRIEDMAN: No. In the past it was more G-d's doing than our doing. In the past, when we had a great teshuva movement - for example in the time of Purim - it was because G-d performed the miracle and blew us away, and we were so inspired and so moved by it that we did teshuva. But it was really His doing. The same is true about coming out of Egypt, and Chanuka. Whatever it was - it was always His doing.

HANDELMAN: Wasn't the Chassidic movement in its origins a teshuva movement - wasn't that the Baal Shem Tov's call?

FRIEDMAN: Yes. The Baal Shem Tov described it as preparation for the Moshiach. It has been a 200-year project.

HANDELMAN: Why then do you say that teshuva is a phenomenon unique to our generation?

FRIEDMAN: Because of the fact that Yiddishkeit is on the rise, not on the decline. Fifty years ago, people were predicting that Judaism was over, that it was irrelevant, no longer served any purpose, and that in a few years it would be gone. It's certainly not gone.

HANDELMAN: Yet that has been the case throughout Jewish history, hasn't it? People have always been predicting the demise of Judaism, and it hasn't ended - so one might still argue that there's nothing radically different about our era as opposed to previous historical eras.

FRIEDMAN: But the teshuva phenomenon is different. In the past, people predicted that Yiddishkeit would die. It didn't because those who were religious stayed that way. But we never had this mass return of people who have no reason to return.

HANDELMAN: Well, you describe it as a "mass" return but statistical studies of the Ba'al teshuva movement have claimed that numerically it is very small. The number of actual Ba'alei teshuva who return to observant Judaism compared to the number of Jews who are leaving, intermarrying, or who don't even belong to a synagogue, is minimal.

FRIEDMAN: I'm not talking about the Ba'al teshuva per se, that handful who go off to yeshiva. I'm talking about the general return to more tradition rather than less, more Jewishness rather than less, even among the Reform. So there is, again, an attitudinal change.

HANDELMAN: Still, one could reasonably predict that just as many Jews will marry out of the faith as will make those attitudinal changes. Fifteen years ago the intermarriage rate was much lower than it is today - so one could also look at it the reverse.

FRIEDMAN: Yes, I suppose one could. But that's not news. The fact that there's a dropout rate, the fact that there is assimilation, is understandable. It's reasonable. It's not a miracle. If you don't teach and you don't inspire, time wears away at you. It's been 3 ,000 years since we stood at Mt. Sinai - what do you expect? The miracle is that people pick themselves up and decide to be more observant rather than less observant.

HANDELMAN: This return to roots is a big trend in America among many ethnic groups, not only the Jews. It's a conventional part of American culture today.

FRIEDMAN: That's part of the miracle.

HANDELMAN: Why is it a miracle?

FRIEDMAN: The prophecy about Moshiach is that Eliyahu will come and he will return the parents to Yiddishkeit through their children. When you have a return to tradition, you're basically going upstream. Tradition comes down. The parent gives it to the children, and the children give it to the grandchildren. But for the grandchildren to pick it up when the parents didn't have it, this is going against nature.

Today, the only way to be Jewish is by doing teshuva, even for those who are born in a religious family. You have to opt for Yiddishkeit, and it's not given to you on a silver platter as it was in the past. So today we have a very voluntary and democratic kind of Judaism that never existed. People predicted that if you would allow people to choose, they would never choose Judaism. But they are choosing it. And even amongst the most assimilated, there are intermarried couples who bring their children to yeshivas and day schools because they want their kids to hold onto that Judaism. So intermarriage is not what it used to be, either. Intermarriage used to mean, "I quit." Today, people intermarry largely out of ignorance, not out of rejection.

What is also unique is the approach the Rebbe has taken in the last 40 years: that every Jew is Jewish, and every Jew wants to do mitzvos, and no Jew can sever his or her ties with G-d, and no Jew is ever lost. And indeed here you have people who are intermarried, totally ignorant, totally assimilated, but they want to be Jewish, and they don't hesitate to come to a rabbi and say, "Teach me."

HANDELMAN: But, take for example, German Jewry at the turn of the century. The situation there was very similar to that of American Jewry today. The parents had emerged from the shtetls of Eastern Europe, Germany had liberalized, and Jews could now enter universities and become citizens. These Jews left Judaism and assimilated. And later, there was a movement to return to Judaism by their grandchildren, for example Buber, Scholem and Rosenzweig. So I could well argue that it has happened before, and there is nothing unusual in this trend of return.

FRIEDMAN: Even if I were to go along with you, the few individuals like Buber and Rosenzweig did not really start a mass movement back to Judaism They wrote a book, people read it and that was the end of it. The assimilation continued.

HANDELMAN: Are you saying that this is a generation of teshuvah and that the core message of Moshiach is teshuva?

FRIEDMAN: Yes. As Rav says in the Talmud, all we need is to do teshuva and Moshiach comes, for all the predestined dates for the redemption have already passed (Sanhedrin 97b).

HANDELMAN: But why has the Chabad movement recently begun putting such a great emphasis on the idea of Moshiach Now? Why specifically now?

FRIEDMAN: The primary reason is that the Rebbe is saying that now is the time. And how are we going to know when Moshiach comes if not by listening to the experts? In addition to that, the Rebbe sees the miracles of the Gulf War and Eastern Europe as miracles of special historic significance, not just miracles of survival as we had for thousands of years.

HANDELMAN: One might wonder, though, whether there is anything "messianic" about these miracles ? Saddam Hussein is still in power, the former Soviet Empire is in economic chaos, the Syrian dictator Assad has gained renewed influence in Middle East politics, etc.

FRIEDMAN: Of course, the problems are far from over. But the miracle is the change in attitude for the good. What is happening today is that quite suddenly there is a recognition of ideological evils and a change in moral attitude.

HANDELMAN: Here again, one might also think of these events as just part of another cycle in history. That is, there are always periods of great reform and progressive hope, and then a regression to oppression and war. Hearing about this new emphasis on Moshiach, some people fear that you're setting yourself up for disappointment, and that it's very dangerous to read into these events some impending arrival of the Moshiach, because it hasn't happened for the last several thousand years.

FRIEDMAN: That's exactly true, and that's why it has to happen now. This fear of disappointment, I think, is a very invalid and insubstantial argument. There's always a chance that we might fail in the things we hope for, the things we work hard for. But that is not an argument against doing it.

HANDELMAN: Nevertheless, in the past in Jewish history, when Messianic movements have arisen, such as Bar-Kochba or Shabbetai Zvi, the resulting disappointment was disastrous for the Jewish people.This disappointment is not a simple thing, it's not like being disappointed in love -

FRIEDMAN: The stronger the virtue, the greater is the damage if it doesn't work. But we should distinguish between today and the past failures of Bar-Kochba and Shabbetai Zvi. Really the two are very different: Bar-Kochba didn't turn out to be a disaster; he just didn't accomplish the goal. Shabbetai Zvi turned out to be a disaster. But what they all have in common, all the past Messianic fervor, is that they happened in a time of great trouble, when people were really desperate, when they had reached the bottom of the cycle, and the only way to go was up; and it had to be Moshiach - which is understandable. When things are that dark, you have to hope for something, you have to look forward to something.

On the other hand, it is still a virtue and a compliment to the Jewish people that our faith is so strong that for 3,000 years we have been consistently confident of his arrival. And what's unique about this time around is that we're doing very well. There is no great trouble. Things are relatively good for Jews today.

HANDELMAN: Many people agree that the concept of Moshiach is important in Judaism, but point to passages in the Talmud which say that we mustn't speculate about these things - that we can anticipate Moshiach, but we're not supposed to inquire into whom it is or talk about signs of the times.

FRIEDMAN: On the one hand, the Talmud in Sanhedrin says that the Sages were very unhappy with people who set dates and made predictions about the time of Moshiach's arrival. But on the other hand, anyone who doesn't expect Moshiach every day is a heretic. So how do we reconcile this?

HANDELMAN: How do we?

FRIEDMAN: If the average person were to start making predictions and say, "I think according to the signs, to the stars, to the this, that, and the other, that Moshiach is coming tomorrow," that's wrong. Moshiach is coming today, always today, never tomorrow, never next week or next month, because we're not supposed to rely on signs. We're supposed to believe and trust that G-d said that He's going to send Moshiach, and G-d will send him today. That's the only resolution to this kind of conflict.

So on the one hand, yes, it's true that we shouldn't play around with predictions. But on the other hand, if somebody says, "I know Moshiach and he's alive today," that's great -

HANDELMAN: You just said a minute ago that it's wrong for every Tom, Dick, and Harry to start making these predictions.

FRIEDMAN: We're not talking about predictions. The predictions are not kosher. But if somebody says, "Moshiach is here; I know someone, and he is Moshiach," that's fine.

HANDELMAN: In the passage you quoted earlier, Maimonides says you can "assume" someone is Moshiach, but you don't know it for sure unless certain conditions are met.

FRIEDMAN: Right. Assume it, and hope it, like Rabbi Akiva did. He went and carried Bar Kochba's armor for him.

HANDELMAN: But as with Shabbetai Zvi, we have seen that when people do get very worked up about Moshiach and they're wrong, the consequences are bad.

Moshiach is coming today. Always today Never tomorrow.

FRIEDMAN: But how can you reconcile this fear of a false Moshiach with your belief in Moshiach? What does your belief in Moshiach consist of if you're afraid that he might be a false Moshiach?

When the real Moshiach does come, what are we going to say? Who's going to believe him? Are we going to say, "Got to be careful - remember Shabbetai Zvi?

HANDELMAN: Still people find finger-pointing very unsettling. They feel that it's very dangerous to point to someone and claim that he is the Moshiach.

FRIEDMAN: If people can point a finger to someone and say, "This is Moshiach," that simply shows how alive and vibrant their faith in Moshiach is. Whether this person is or is not Moshiach is irrelevant.

HANDELMAN: Would you say that it is irrelevant even if, for example, we decide on the wrong person? New religions have been formed as a result of the belief that certain persons were the Moshiach, and Judaism suffered considerably when these other religions persecuted the Jews for refusing to accept these "Messiahs."

FRIEDMAN: The same is true of belief in G-d: The belief in G-d has been the cause of a lot of suffering, too. If you believe in the wrong god, or you start fighting over who G-d is, it also causes trouble.

But you can't use the abuse of something as an argument against it. And the same thing holds true for attributing great powers to an individual. Just because there was a Jim Jones and a Jim Swaggart, are you going to say that you shouldn't believe in anybody? It's because we don't believe in the right people that these charlatans find their way into those positions. If we're open to the idea that somebody alive today is Moshiach, whether it's some Kabbalist in Israel or a Rosh Yeshiva in Lakewood, that would indicate that our belief in Moshiach is alive and healthy and well. Then when Moshiach comes, there'll be no problem.

HANDELMAN: And what we would imply by these claims is that this is a person who is a great leader and a teacher - not a miracle-worker, but somebody who could bring the potential for goodness into the world if we paid more attention.

FRIEDMAN: Yes.

HANDELMAN: In the Talmud (Sanhednn 98b) the Sages have an interesting discussion about the name of Moshiach. Each school claims that he is their teacher. The school of Rav Shila said his name is Shiloh, and the school of Rabbi Yannai said his name is Yinnon, and the school of Rabbi Haninah said his name is Haninah, etc. This passage seems to support your interpretation.

FRIEDMAN: Yes, the commentaries say that each one thought that his Rebbe was Moshiach.

HANDELMAN: Then why is it, do you think, that such interpretations of Moshiach make many people so uncomfortable? Why are people so afraid to identify a potential Moshiach?

FRIEDMAN: For a long time, since the Enlightenment movement, Jews have been a little bit reticent on the subject of Moshiach because it was one area in which the enlightened Jew ridiculed the observant Jew's totally blind faith.

Moshiach is really probably the only subject or the only issue in Jewish life that is completely blind faith. Anything else can be explained by historical or theological reasoning, but Moshiach's coming is totally beyond reason: G-d said he's going to come, so he's coming. And there was a time when rational, logical arguments reigned supreme. We were a little bit ashamed of the fact that we held this totally irrational belief, and so we soft-pedaled it and we stopped talking about Moshiach in public, because it would only open us up to ridicule. I think that still lingers.

We're ashamed, because we don't know how to justify it, don't know how to explain it, can't rationalize it. It is our faith. And we're not comfortable with faith. We're comfortable with logic.

HANDELMAN: Maybe we should talk a little about the nature of the Messianic era itself. I know that the Talmud makes distinctions between the pre-Messianic era and the Messianic era itself.

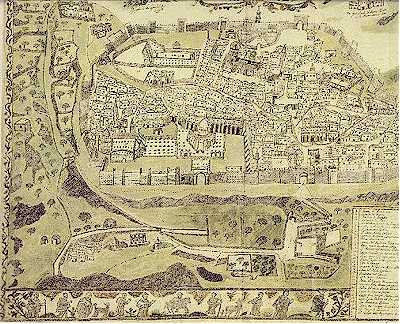

FRIEDMAN: There will be a time called the "Days of Moshiach" (Yemos ha-Moshiach), which is different from "The World to Come" (Olam ha- ba). In Yemos ha-Moshiach, nature does not change. You don't have any resurrection of the dead, and you don't have disruption of nature. All you have is total universal goodness and morality. And that would mean that nation does not oppress nation, that there is no suppression of religion, and so on. And we're beginning to see that today. Take the fact that you really can't find any place on the globe where a Jewish community is not permitted to practice Judaism.

HANDELMAN: What about Iran, for example?

FRIEDMAN: Jews are allowed to practice Judaism in Iran. If you practice Zionism, then you're killed, but if you go to daven with your tefillin? No, nothing at all.

In Saudi Arabia, it's forbidden, but there are no Jews there. And this overall global freedom for Jewish practice has no precedent in the last 2,000 years. So in that sense there's a geula [redemption] for Yiddishkeit in the world.

To return to our point, in the "Days of Moshiach," morality becomes the norm, or maybe the primary pursuit of mankind. "The World to Come" (Olam ha-ba), however, is when nature itself starts to change, when earth becomes heaven. And then it's eternal, and there's no death.

HANDELMAN: You are saying that there exists this Messianic potential, and you see it in the signs today. But it could very well be that the potential might not be realized in our generation, even though we might be very close, right ?

FRIEDMAN: When you say that you believe that Moshiach is coming, then you can not entertain the possibility that he's not coming.

HANDELMAN:

Why not?

HANDELMAN:

Why not?

FRIEDMAN: The belief in Moshiach is not the belief in a possibility. The belief in the coming of Moshiach is the belief in the fact that he's coming.

HANDELMAN: Yes, but doesn't the "fact that he's coming" mean that at any given time it is only a possibility ? There's a belief that ultimately he will come, but not necessarily today. The belief is in the potential for him to come every day.

FRIEDMAN: Now there's the difference between the way the Rebbe looks at emunah [faith] and the Moshiach, and the conventional approach. The conventional approach is that the belief in Moshiach means that you have to believe that Moshiach could come. That's not correct.

HANDELMAN: Why?

FRIEDMAN: That's not faith at all. To say that there's a possibility - there are all sorts of possibilities. That's not "complete faith" - emunah shleimah. Emunah shleimah means you cannot conceive of a world today without Moshiach. Not that he could come, but that he must come .

And Moshiach's coming is dependent on our doing God's will. We did his will; I did my best today; what else does He want?

HANDELMAN: Maybe you did your best in fulfilling the mitzvos today, but not everybody did. Does the promise, that Moshiach will come today, "if you do My will" mean that everyone must do G-d's will?

FRIEDMAN: That's a genuine point of contention. Are we good enough? Have we done enough? Are we ready for Moshiach? The Rebbe says we are.

HANDELMAN: Why does he think so?

FRIEDMAN: Because the Rebbe looks at us as a historical collective, not just as one generation. And the Jewish people, having gone through 2,000 years of this horrible exile, are more than ready, and more than deserving.

HANDELMAN: Why, because we have suffered?

FRIEDMAN: Yes, not only suffered, but we have suffered well. We have excelled in suffering, without losing our faith.

HANDELMAN: So your point is that there is a crucial difference between a certain view of the Moshiach as a "possibility," and an emunah shleimah which is the conviction that he is coming.

FRIEDMAN: Yes, emunah shleimah is the conviction that he is coming now.

HANDELMAN: That's what we're tangling about. Even if I am obligated to expect that Moshiach could come now, I don't know that for sure. So I must be open to the possibility that he may not come now. I do not have the chutzpah to interpret every single sign. I think this is the core of our discussion.

FRIEDMAN: Even if you don't interpret the signs, you are commanded to believe that Moshiach is coming today. Not that he "might" come. We say that every day in the prayers and Maimonides based one of his thirteen principles of faith upon this: "Ani ma'amin b'emunah shleimah." Not that he could come, but as the text says, "I believe with total faith in the coming of Moshiach": That's the first part of the statement. What does it mean to believe with perfect faith? That even though he hasn't come in 2,000 years, yet every day I expect him to come.This is the definition of emunah, of faith - in anything, not just in Moshiach. Emunah means that this is something that has to be. Now, there are those things that can possibly exist and then there is absolute, necessary existence.

If you believe that Moshiach is coming then you cannot entertain the possibility that he may not come

HANDELMAN: How is that specifically the definition of emunah?

FRIEDMAN: Emunah is supra-rational. It is an irrational conviction that something just has to be. And it's not just Moshiach. We all have this quality in some way. To take an example: many of us are convinced that people are basically good; now that doesn't come from experience

We might ask, what is the definition of an ideal? An ideal means a conviction about how things must be, not how they are. And therefore you can't come to an idealist and say: "What do you mean, you believe people are good? Look at so-and-so who is a mass murderer." That will have no effect on his or her idealism, because their idealism states that this is how it must be, and if it isn't yet, then it will be, because it must.

HANDELMAN: Are you perhaps saying that we get that idealism from a higher source - that these notions of Moshiach and goodness come to us from a kind of revelation?

FRIEDMAN: Yes.

HANDELMAN: But how can we be sure that this particular irrationality is trustworthy and not a hallucination?

FRIEDMAN: How do we trust any of our ideals? Why do we spend billions in search of a cure for cancer? Because you're convinced: it just can't be that there is no cure. Now, what convinces you of that?

HANDELMAN: I could argue that my faith in modern medicine has been backed up by evidence. It's not irrational to think that knowledge advances, because I have in fact seen cures for many things that were not previously curable.

FRIEDMAN: Right. But when they started the research on cancer, we were just as certain of it then. So it's not the evidence that's convincing us that there is a cure. It's a belief that we just simply cannot accept a world in which there are incurable diseases and evil.

HANDELMAN: This optimism - the need to believe that there is a light at the end of the tunnel, can be very adaptive. It can help us go on in times of great trouble. On the other hand, optimism can be destructive. It can blind us to reality. It can also, as some critics of Lubavitch have said, lead to "passivity" in relation to the needs of the moment.

FRIEDMAN: Until now, Lubavitch has been accused of being too aggressive. We're coming on too strong, we're pushing too much, we're going too far - all of a sudden we're passive.

But of course, if you start noticing a passivity resulting from the belief in Moshiach - that's not a belief, it's a cop-out. If you believe in Moshiach, you become more active, you don't become less active.

HANDELMAN: Some critics have argued that an intensified Messianism is dangerous because it can lead people to take very extreme and unrealistic political positions. What are the connections of Messianism, as you have described it, to political action is Israel?

FRIEDMAN: I think you should take Moshiach the way it's meant to be: that you merely intensify all the things that G-d wants of you and all the things that the Torah wants from you. If Moshiach is Moshiach, then mitzvos become more natural and goodness becomes more natural. You don't start projects that are new, that are different. Whatever we're supposed to do in Israel, we were supposed to do with or without Moshiach.

HANDELMAN: And what are we supposed to do in Israel?

FRIEDMAN: Make sure that the Jews in Israel are safe. That's priority number one. So as the Rebbe says, fortify the borders. Make no concessions, because it would be dangerous to do so. That's a law in Shulchan Aruch [Orach Chaim, Ch. 329]. It's not Messianic.

HANDELMAN:

Suppose I'm not a Lubavitcher and I still want to become more active, what should I do ?

HANDELMAN:

Suppose I'm not a Lubavitcher and I still want to become more active, what should I do ?

FRIEDMAN: Talk up Yiddishkeit. Assume that your Jewish neighbor or business associate wants to become more observant, and all you have to do is show him how and give him the opportunity and expose him to a mitzvah - and that will take

HANDELMAN: And why will that bring Moshiach?

FRIEDMAN: Because Moshiach could have come at any moment, right? If he decides to come, he comes. But if he's waiting all these years, it must mean that he doesn't want to overwhelm us.

The coming of Moshiach can't be one of these glassy-eyed, overwhelming experiences like the Exodus from Egypt or the giving of the Torah at Sinai, because those things just don't last. Because again, it's G-d doing it, not us. It's the initiator, but not the response. So Moshiach can't come unilaterally, because then it's not Moshiach - it's just another good event in our long history of miracles and revelations.

In order for Moshiach to come without disrupting us, without blowing us away, we have to have some awareness or some readiness, or some ability to handle the idea that the world is becoming good, that evil and suffering are going to end. Like the bumper sticker that says "Visualize world peace." If you can't make it happen, visualize it; at least be able to conceive of it. So if we get more and more people thinking, "Yes, it is time for the world to become good," maybe we could actually realize that which everyone has always insisted and believed: that the world will some day be good.

But why some day? Why not today? If we can just get that thinking, then we're ready for Moshiach. We don't have to do it. We just have to be open to it.

HANDELMAN: I'm interested in what you just said - that the arrival of Moshiach is not a glassy-eyed ecstatic event. I think most people do have that idea in mind, perhaps because of the influence of the non-Jewish notions of Moshiach.

FRIEDMAN: I agree. That's the idea that Moshiach comes in a flash - one moment he's not here, the next moment he's here, and everything is perfect. But that can't happen because that means that G-dliness has not come down to earth.

HANDELMAN: Is that, then, the ultimate meaning of Moshiach, that "G-dliness has come down to earth?"

FRIEDMAN: That G-dliness becomes obvious. It's no longer a miraculous spiritual thing. It's obvious.

HANDELMAN: All in all, you're interpreting the whole idea of Moshiach's coming as a kind of a gradual recognition of G-d, and at the same time, you're saying that there will be a new form of revelation. There is the gradualness which you just described, and then there is something really new and different.

FRIEDMAN: It's going to be a radical change, but not disruptive. A grass-roots kind of a thing, not revelation from heaven, but revelation from within, so to speak. It'll dawn on us, it won't shock US.

HANDELMAN: And what precisely will dawn?

FRIEDMAN: That G-d is real, and that goodness is real, and that evil is false, and that darkness is only imaginary.

HANDELMAN: But evil is real, isn't it? People do suffer, people are hungry, people are homeless, people are ill.

FRIEDMAN: Yes. But the idea that Gam Zu L'Tovah ("this is for the best" ) which today is something we have to bite our tongues on when we say - this will become obvious when Moshiach comes. We will see the goodness in what previously appeared to be evil.

HANDELMAN: Someone recently wrote that he's no longer waiting for the Moshiach. His point was, "Where was the Moshiach when we really needed him, such as during the Holocaust? He's too late."

FRIEDMAN: That's a good question. I'm waiting to ask Moshiach myself. When Moshiach comes we will find out why, wherefore.

HANDELMAN: How will we find that out? It's not Moshiach who is going to give all the answers because Moshiach is just a human being, right ?

FRIEDMAN: He may have the answer, or the answer may just become apparent of itself. When the darkness lifts, we begin to see clearly.

But it's a good question. Like the Talmud says "teiku" - that Eliyahu will answer all the questions and problems in the times of Moshiach. So this is one of those questions we can't answer until Moshiach comes.

HANDELMAN: As I understand what you have said, the objective is to bring Moshiach, and to do that we need to increase in the observance of Torah and mitzvos, and to get others to do the same. But could we accomplish this more effectively without talking about Moshiach - since the topic creates so much controversy?

FRIEDMAN: There are those who believe that you should get people to do mitzvos without telling them about G-d, because G-d is a difficult subject for people. No. You can't do that. If your enthusiasm is coming from the fact that you believe Moshiach is imminent, then you should share that with others. Why hide it? What are we apologizing for here?

HANDELMAN: So being ready means helping other Jews, and talking about Moshiach -

FRIEDMAN: Being ready means that if he shows up today, you will not be shocked. You won't be speechless. Ready means that we won't be overwhelmed. Moshiach does not want to overwhelm us, because if he were going to overwhelm us, he could have come l00 years ago.

I think that it is important to understand that much of the fear and discomfort with the excitement about Moshiach comes from associations people make with something apocalyptic and with the disruption of normal life - of packing up and waiting to be flown to Jerusalem. It is important to disabuse ourselves of this notion that Moshiach comes and blows everything to pieces. Because, in fact, this isn't the way it is.

Somebody was visiting the Lubavitch World Headquarters in Brooklyn recently, and was shocked to find that it is in the process of elaborate renovations. He thought that the Lubavitchers' excitement about Moshiach implied that people would pack their bags and stop all normal activity. What he found, however, was quite to the contrary. We are not drifting away and losing our grounding in reality. In fact, the day-to-day, normal activity gains momentum because of this excitement and this desire to bring Moshiach.